Summary

Central America is one of the regions that is most vulnerable to climate risks in the world (Kreft, S.; Eckstein, D. 2013). The Central American dry corridor is a dry tropical forest ecoregion that spans from Guanacaste in Costa Rica to southern Mexico, which holds nearly 7.5 million people whose main socioeconomic activity is rainfed agricultural production, mainly involving staple grains such as maize, beans, and rice, as well as cattle farming. This area is characterized by a unimodal-trend rainfall regime, i.e., rain is concentrated into five months and the rest of the year there is extreme drought. This means that many farmers, most of whom do not have irrigation, may only produce food and have farming employment during half the year, a factor that causes poverty, hunger, unemployment, and migration.

To address the negative effects of drought in Central America, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and the Fondo Latinoamericano para Arroz de Riego (FLAR) implemented a project cofinanced by the Fondo Común para los Productos Básicos fund in Nicaragua and Mexico, which spanned over four years (2008-2012).

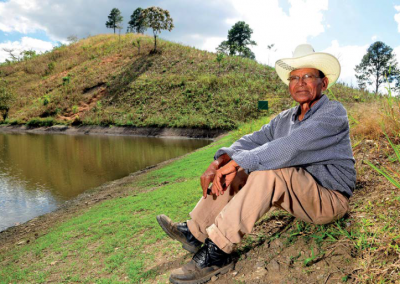

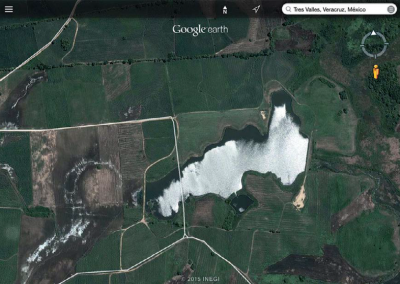

The project sought to introduce and promote “water harvesting” as a practice for adapting to climate change and as a continued-production economic and sustainable alternative, by transforming rainfed irrigation systems in dry areas and tapping into rainwater runoff. The project worked with small family producers of staple grains. It helped build pilot reservoirs and install several irrigation systems on their farms, as well as validate agronomic crop management technologies used for high productivity with irrigation.

The project placed special emphasis on human capacity development, family empowerment, and technology transfer, because it considers these factors to be key to the sustainability and scaling-up of water harvesting over time.

Similarly, the active involvement of countries’ municipalities, producer associations, and environmental authorities was crucial to implementing the initiative and disseminating technology to other regions.

For six crop cycles, the project proved that by irrigating through water harvesting and using better technologies, agricultural and livestock production, as well as nonagricultural rural business, are feasible during the dry season. Water has enabled annual yields of staple grains (maize, rice, and beans) to double or even triple, as well as helping diversify with other crops, water cattle, and produce tilapia.

The project shows that farmers do not need to migrate with cattle in search of better conditions; this allows for maintaining family unity and generating new employment options and better income within farmers’ own farms.